Chapter 4A - 2

Treaties in Canada

Canada only became a country in 1867 and was trying to build a strong, new nation. To do this the government needed more populations so they encouraged immigrants to come and settle in Canada (Nishnawbe-Aski Nation: 27-28). Settlers mainly came from Europe, towns grew up in many places and people migrated across Canada to find work and settle farms. By this time in Canada, the population of newcomers had outgrown the First Peoples (ibid). Therefore, we were in the way of “progress” and certainly in the way of railroads, clear cutting forestry, mine development, surveying, road construction and exploration.

So, in the late 1800s in Canada, many treaties were being signed reluctantly by First Peoples so they could find some relief from all the pressure to their lands.

In the 1800s, explorers, geologists, prospectors and surveyors traveled through Northern Ontario assessing it as I’ve said, for resource development such as railroad construction, mining, hydroelectric energy, forestry, and agricultural uses. Our peoples knew of the strangers in our land and even petitioned the governments of Ontario and Canada as early as 1889 to protect our lands (Long 1978: Introduction, 7, 18, 21). The government knew that our lands were being encroached on but their view was that “civilization” “settlement” and “progress” was inevitable in the north. As well, the resource potential for the governments included gold, silver, pulp/paper, and electricity that would make them wealthy and economically stable. But first the governments needed to deal with our peoples, to extinguish our claims and secure the title to our land so that development and settlement was unobstructed (Nishnawbe-Aski Nation 1986: 32). And the legal instruments they had been using all over Canada to deal with First Peoples were treaties.

Frank Pedley, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs wrote in 1904, “The strong reason by which this Government is actuated in the making of the treaty is the old and well-established rule that a way must be smoothed for exploration, location of railway lines and construction, by extinction of the Indian title” (Long 1978: 9). As well, Duncan Campbell Scott, Commissioner of the Department of Indian Affairs speaking of the Treaty No. Nine interactions with our peoples in 1905 said:

"They were to make certain promises and we were to make certain promises, but our purpose and our reasons were alike unknowable. What could they grasp of the pronouncement on the Indian tenure which had been delivered by the law lords of the Crown, what of the elaborate negotiations between a dominion and a province which had made the treaty possible, what of the sense of traditional policy which brooded over the whole? Nothing. So there was no basis for argument" (Long 2006:12).

At Fort Hope, Treaty Commissioner George MacMartin described in his journal the way Duncan Campbell Scott explained the treaty to the Anishiinaabe men:

“[T]he King has sent the Commission to see how his people were and to enter into a Treaty with them, and that the King wished to help his subjects and see that they were happy and comfortable, giving them as a present this year $8 per capita and an annuity for ever of $4 per annum, also setting aside for their sole use and benefit a tract of land 1 square mile to each family of 5 that no white man should put his foot on without their permission” (ibid: 14).

At the end of their treaty signing mission in Northern Ontario, the Treaty Commissioners wrote to their superiors, “The Indians, and we confidently believe do not, expect any other concessions than those set forth in the documents to which they gave their adherence” (Morrison 1986: no pagination). To read more about the Treaty Commissioners route in 1905 to our lands go to this link http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/al/hts/tgu/pubs/t9/trty9-eng.asp.

Now, I have briefly explained the background as to why the governments wanted our peoples to sign the treaties. It was because they wanted to make sure the land was open to settlement and railroads for easier access to the resource development they had in mind for the north. As well, you can see by the Treaty Commissioners comments that their attitudes and beliefs were focused on extinguishment of our peoples’ title to the land and secure government ownership of our lands.

References

Text Sources

- Hookimaw-Witt, Jacqueline, 1998

"Keenebonanoh Keemoshominook Kaeshe Peemishikhik Odaskiwakh -We Stand on the Graves of Our Ancestors: Native Interpretations of Treaty No. 9 with Attawapiskat Elders." MA Thesis

Peteborough: Trent University.

- Knudtson, Peter and David Suzuki, 1992

Wisdom of the Elders.

Toronto, ON: Stoddart Publishing Co. Limited.

- Long, John S, 1978

Treaty No. 9: The Indian Petitions, 1889-1927.

Cobalt, ON: Highway Book Shop.

- Long, John S, 1978

Treaty No. 9: The Negotiations, 1901-1928.

Cobalt, ON: Highway Book Shop, 1978.

- Long, John S, 1985

Treaty No. 9 and fur trade company families: northeastern Ontario's Indians, halfbreeds, petitioners and Métis. In The new peoples: being and becoming Métis in America, Jacqueline Peterson & Jennifer S.H. Brown eds.

Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, pp. 137-162.

- Long, John S, 1989

"No Basis for Argument: The Signing of Treaty Nine in Northern Ontario, 1905-1906."

Native Studies Review 5, no. 2: 19-54.

- Long, John S, 1993

"The Government is Asking you For Your Land": The Treaty Made in 1905 at Fort Albany According to Cree Oral Tradition. Schumacher: John Long.

- Long, John S, 1996

"Who Got What At Winisk?"

Beaver 75, no. 1: 23-31.

- Long, John S, 2006

How the Commissioners Explained Treaty Number Nine to the Ojibway and Cree in 1905. Ontario History.

Vol XCVIII: (1) 1-29.

- Louttit, Elder Agnes, 2008

Personal communication about starvation experience.

Moose Factory: Home residence.

- Macklem, Patrick, 1997

"The Impact of Treaty 9 on Natural Resource Development in Northern Ontario." In Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference, ed. Michael Asch, 97-134.

Vancouver: UBC Press published in association with the Centre for Constitutional Studies, University of Alberta.

- McDonald Miriam, Arragutainaq Lucassie, and Zack Novalinga, 1997

Voices from the Bay: Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Inuit and Cree in the Hudson Bay bioregion.

Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Arctic Resources Committee and Environmental Committee of the Municipality of Sanikiluaq.

- Morrison, James, 1986

Treaty Research Report: Treaty Nine (1905-06).

Ottawa: Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

- Nishnawbe-Aski Nation, 1986

A History of the Cree and Ojibway of Northern Ontario.

Timmins: Ojibway-Cree Cultural Centre.

- Ojibway Cree Cultural Centre, 1999

But Life Is Changing, Vol 1.

Timmins: Ojibway and Cree Cultural Centre.

- Ojibway Cree Cultural Centre, 1999

But Life Is Changing, Vol 2.

Timmins: Ojibway and Cree Cultural Centre.

- Ojibway Cree Cultural Centre, 1999

That Is What Happened.

Timmins: Ojibway and Cree Cultural Centre.

- Spence, Greg, 2008

Personal Communication: Treaty No. 9 Language.

Moose Factory: Home residence.

Visual Sources: Maps, Websites, Archival Material

- Map of Canada (showing Moosonee and Moose Factory)

http://gregq.tripod.com/MAP.GIF (05/17/08) - Photograph of Moose Factory Island

http://www.creeadventures.com/AUT_0166.JPG (05/17/08) - Photograph winter camp

http://www.ourvoices.ca/images/winisk_wintercamp.jpg (05/17/08) - Fur trade

http://www.turtletrack.org/Issues03/

Co04192003/Art/FurTrade.jpg (05/17/08) - Mushkegowuk family in the bush

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter3a_big.jpg (05/17/08) Laurentian University Archives, Diocese of Moosonee. - Mushkegowuk Peoples at English River receiving candies, 1905

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter3b_big.jpg (05/17/08)

Library and Archives of CanadaPA-059546 - Congregation outside St. Thomas Church, Moose Factory, (ca early 1900s)

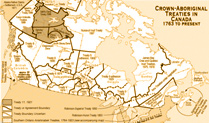

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter3c_big.jpg (05/17/08) Laurentian University Archives, Diocese of Moosonee. - Crown-Aboriginal Treaties in Canada, 1763 to present

http://bclearningnetwork.com/LOR/media/fns12/COURSE_8730771_M/my_files/onlinefiles/22a_treaties.gif (05/17/08) - Treaty No. Nine Commissioner Duncan Campbell Scott

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter4b_big.jpg (05/17/08)

The James Bay Treaty signing party at Fort Albany. Standing: Joseph L. Vanasse (L), James Parkinson (R) of NWMP. Seated: Commissioners Samuel Stewart (L), Daniel McMartin, Duncan Campbell Scott (R) Foreground: HBC Chief Trader Thomas. 1905. Digital Image Number: I0010627.jpg Duncan Campbell Scott Fonds Item Reference Code: C 275-2-0-1 (S 7546) Archives of Ontario. - Unknown Mushkegowuk Peoples in James Bay, (ca 1900s)

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter4d_big.jpg (05/17/08) Laurentian University Archives, Diocese of Moosonee - Chief Moonias, Treaty Signing, Fort Hope, 1905

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter4e_big.jpg (05/17/08

Library and Archives of Canada. PA-059534 - Blind Chief Missabay addressing the assembly before the feast held after the James Bay Treaty signing ceremony, Osnaburgh House, July12, 1905

http://ao.minisisinc.com/WEBIMAGES/I0010717.jpg (05/17/08) Duncan Campbell Scott fonds. Item Reference Code: C 275-1-0-2 (S 7600). Archives of Ontario. - The signing of the Treaty at Winisk, Ontario. Left to right, standing: Father Martel, Indians John Bird, Xavier Patrick and David Sutherland, Dr. O'Gorman and J. Harris, H.B. Co. Post Manager. Seated: Commissioners Walter C. Cain and H. N. Awrey. July 28, 1930. (05/17/08)

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter4g_big.jpg Library and Archives of Canada. PA-094963 - Treaty No. Nine, the James Bay Treaty

https://www.pathoftheelders.com/templates/pote/images/essay/chapter4h_big.jpg (05/17/08)

Appendix

Creation Story

Two friends, one man and one woman, were walking on an open plain. It seemed to go on forever. Yet, they saw something far ahead in the distance. It looked like a small animal. They went towards it to see what it was. As they came nearer, they realized it was the Great Spider.

"Where are you going?" the Great Spider asked when they were near. "We are looking for a home, a place where we can live," they replied.

"There is a place down there," the Great Spider said, pointing down below him. "It is a vast land. In the winter, it snows and gets very cold. In the summer, it rains and gets very hot. But this land is very good. If you wish to go there, you can. From where I am sitting now, I can lower you down." Then the Great Spider warned, "But, you have to do exactly what I tell you. If you do not, things will not work out well for you."

After some thought, the man and woman replied, " We will go. It will be our home."

"Then climb in," said the Great Spider. He had already made a huge bowl-shaped container with his webbing.

"Climb in and I will lower you down," he said and then attached one end of his spider web to the container. The man and woman climbed in.

"As I lower you, neither of you shall look over the edge. If you do, you will end up in a dangerous place. Keep your heads down until you have landed," commanded the Great Spider.

The man and woman nodded in agreement and climbed in. Down, down, down, down, they went. It took a long time.

"It’s taking too long, " the man and woman thought.

One of them decided to take a peek and then looked over the side. At that very instant, the webbed container stopped. Cautiously, the man and woman stood up and found that they had been put down in an eagle’s nest on the top of a very tall tree. When they looked closely at the tree, they became frightened. The tall tree had no branches below. There was no way to climb down and it was much too high for them to safely jump down from the tree.

As time passed and while they were wondering what they should do, they noticed some caribou walking along the river toward them. The two called out to the caribou and asked to be helped down.

The caribou replied, "We cannot climb trees. We often stumble, walking on barren ground." They went on their way.

Time passed and then another animal walked along the river. It was a bear. The two called out to the bear.

"What do you want?", the bear asked.

"Can you help us down?", the man and woman asked.

Without saying another word, the bear lumbered away in his very unconcerned manner. He did not feel like helping anyone today.

Then they saw a smaller animal pass by. It was a wolverine. They called out, "Hey! Can you help us down please?"

"Of course," the wolverine replied and quickly scampered up the tree. One by one, the wolverine carried them down safely. The man and the woman were very grateful for this wolverine’s kindness and thanked him warmly. The wolverine was soon on his way.

The man and the woman had safely arrived at their new home. They discovered how to survive on this land. In time, they bore children, and their children had children. The people grew in numbers and spread over the land. They paid honour and respect to the Creator for the vast land, and learned to become a part of it, caring for all living things that provided for them. This is how our people began. (Nishnawbe-Aski Nation 1986: 1-3)

Chapter 4B - 1

The Anishiinaabe and Mushkegowuk People's view of Treaty No. Nine

Kashechewan Elder James Wesley remembered through stories that one of the Commissioners, "held up a bible in his hand to show the seriousness of their intentions" (Long 1989: 37). He went on to say our peoples were promised, "a sawmill, housing, schooling, medical services, doctors, gardening tools, vegetable seeds, and livestock" (ibid). Another Kashechewan Elder Hosea Wynne recalled what he had been told:

"According to our grandfathers, in 1867, they went to see the native people to ask them for their land. Their names were David Solomon, David Wynne, John Faries and James Sackaney. I’ll repeat what the old man (David Solomon) said they said when they asked for the land. The Indian Agent and his assistant said they were representing the government and were sent by the government. There was also a doctor and a police officer. He said that’s how many people had come to see them. But there were other people present there. The Indian Agent introduced himself and the other people that were there with him. He said the government came to ask for the land, to be the custodian of the land for the native people. The government would have control, and would take care of the land. This was the first thing he told the native people. The government is asking for your land” (Hosea Wynne in Long 1993: 3-4). Elder Hosea Wynne continued, “Then he stated the terms. The first thing he mentioned is, the government will build you a house, just like the manager’s house. But first, a sawmill where you will make flat wood and a horse to pull boards. This is what the old man (David Solomon) said" (ibid).

But Elder Hosea Wynne stated there was a problem concerning the verbal promises and especially the written treaty, “But there is no agreement in there. Everything that was promised should have been written there. This is not a true treaty, what you see there. These promises are missing. Until you see these (promises) in there, and we see them written – then we will believe in it. We will not believe what is written in there, not until we see what was promised (to us verbally) in writing" (ibid: 5-6)

Elder Hosea Wynne also spoke passionately about what his Elders were faced with:

"This is what we regret on behalf of our grandfathers and we also feel for them. We can’t forget them because they didn’t understand what they were asked when they were asked for their land. They didn’t know about the natural resources that are under the ground, and they didn’t know that there was profit to be made from the trees. Our grandfathers didn’t know that there were these kinds of resources under the ground. But this one, who got rich from these resources, he was positive that there were such resources. Our grandfathers didn’t fully understand what they were asked for. We remember and feel for our grandfathers, when we see how the government has benefited from our grandfathers' land" (ibid: 6-7)

Anishiinaabe Elders from Bear Skin Lake and Muskrat Dam also remembered and viewed the treaty as a relationship of sharing with the governments, and not land surrender or government regulation:

"I can clearly remember when the treaty was signed. We were promised assistance and protection from the government for as long as the sun shines and rivers flow. We were promised that our traditional activities would not be regulated from us" (Elder Jimmy McKay, interviewed 1974 at Bear Skin Lake) (Hookimaw-Witt 1997: 62-63).